Hello and welcome to the final newsletter of 2016 from Remap Consulting. Topics that are covered in this edition include: Are the PCSK9 inhibitors a commercial flop or a slow burner; Can multiple criteria decision analysis enhance HTA decision making and are payers helping or hindering biosimilar market access?

Looking forward to 2017, we are delighted to be presenting to the Masters Biotechnology course at Grenoble University. We have been one of the key authors of EUCOPE’s position paper on international reference pricing which challenges the payer rationale for using IRP to determine price and is expected to be published early in the new year will be published.

Finally and most importantly, we would like to wish you and your families a very happy holidays and an enjoyable start to 2017.

PCSK9 inhibitors – Commercial flop or just a slow start?

In 2015, Repatha (evolocumab) and Praluent (alirocumab) received significant publicity during their launch. These new PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin 9) inhibitors publicity focused on two elements; 1) the potentially huge 54–77% reduction in LDL cholesterol and 2) the ~$14,000 annual US treatment cost (see our article: Are the PCSK9 Inhibitors, Repatha and Praluent, the new Sovaldi?). So how successful has the PCSK9 inhibitors launch been and what are the implications for them in the future?

In commercial terms, both Repatha and Praluent have got off to slower than expected starts, with Repatha achieving global Q3 2016 revenues of only $40 million. The main reasons appear to be the unwillingness of insurers to fund the new treatments, low physician support and the lack of hard outcome data.

One of the major challenges has been the price associated with PCSK9 inhibitors, which launched with a list price of ~$14,000. In the US, it has been reported that discounts of ~50% have been offered to health insurers, which potentially brings down the cost of the PCSK9 inhibitors to a comparable level with European countries. However, even at $7,000/year the cost is still significantly more than the cost of high dose statins and given that patients are likely to be on these treatments for the rest of their lives, the resulting budget impact can be significant. Furthermore, justification of the launch price hasn’t been helped by the US’s Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, which suggested an 85% price decrease (to $2,177 annual treatment cost) was the appropriate price level for these treatments to be considered cost effective.

For those patients in the US that are potentially eligible for Praluent or Repatha, payers have placed barriers to prescription, resulting in restricted patient access. One is the prior authorisation that covers the PCSK9 inhibitors, where doctors have to prove that the patient has hypercholesterolaemia and has already tried two statins. This prior authorisation can consist of over 40 questions and even with the appropriate documentation, physicians have been finding that the insurer’s rejection rate for first time prescriptions was over 77%. After five appeals, over 60% patients wanting to use PCSK9 inhibitors are still not funded by the insurers, highlighting that payers do not currently believe the value of PCSK9 inhibitors, instead preferring the alternative treatments.

Another factor behind the slow uptake has been a reluctance with physicians. Whilst the majority of physicians do believe that the LDL reductions are significant, but not all physicians believe that reduction will translate into tangible outcomes. This, combined with the barriers that are being imposed by payers, is hindering the uptake of the PCSK9 inhibitors.

For physicians and payers to encourage wider use of the PCSK9 inhibitors, evidence needs to be produced regarding the potential significant reduction in cardiovascular (CV) events from these treatments. Both Amgen and Regeneron have initiated long term cardiovascular trials to address this need, which are expected to read out in 2017 (Repatha) and 2018 (Praluent). What level constitutes a significant reduction is another matter, with most physicians stating around a 20% reduction in CV events, whilst some payers have speculated that the reduction in events would need to be closer to 50%. A recent interim analysis for Praluent has provided little insight, as the bar for halting the trial was set at 20% reduction in CV events was not met. Had the outcomes trial been halted early, it would have been a huge boost to both Praluent and Repatha.

So what does this mean for the PCSK9 inhibitors class? Fundamentally, little will change in the management or uptake of these products until the results of the cardiovascular outcomes trials are known and then it will be down to magnitude of the CV reduction that will be important to the commercial success of these molecules. It is clear that a 20% or greater reduction in CV events is required in order to drive wider use of Praluent and Repatha, but the reality may be more nuanced.

There are also a number of interesting implications for other biologics considering to enter similar disease populations like cholesterol reduction. First, even with a significant reduction in surrogate markers, payers still want to be convinced of the clinical outcomes data, particularly if there are other therapies that are currently effectively managing the disease. Second, payers can put in place multiple prescribing obstacles to limit physician uptake if they don’t believe in the treatment or the current evidence base. Thirdly, widespread physician support is not guaranteed if physicians do not believe the price level fully reflects the value of the product.

Finally, it all comes down to price and perceived value. At the moment, both payers and physicians do not believe that at the current price level, Praluent and Repatha offer significant value for widespread use. Both PCSK9 inhibitors have had some success in the UK and Germany where reimbursement is restricted beyond the regulatory label for very small patient populations, which had a high unmet need. This demonstrates that access can be achieved at the current price level, but only for a small subset of patients, which significantly limits the revenue potential for these products. This implies that whilst not failures, it is highly unlikely that Praluent and Repatha will achieve their revenue forecasts, at least in the short term, until the benefit in the broader patient population is demonstrated.

Can multiple criteria decision analysis enhance HTA decision making?

When faced with evaluating alternative treatment options, healthcare decision makers must consider multiple, often conflicting, criteria. Multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) is a potentially useful tool that can be used to support such decision making. For the past few years, the options and feasibility of using MCDA for health technology assessments (HTA) have been explored. Both the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) have published reports that describe and evaluate MCDA’s applicability for HTA.

What is MCDA?

In the literature, MCDA is defined as “an umbrella term to describe a collection of formal approaches, which seek to take explicit account of multiple criteria in helping individuals or groups explore decisions that matter”. At its core, MCDA is useful for:

- Dividing the decision problem into smaller, more understandable parts

- Analysing each part

- Integrating the parts to produce a meaningful solution.

During the analysis step, a transparent, mathematical approach is often adopted. This necessitates that evidence is expressed in a quantifiable, numerical way.

How do MCDA processes compare to current HTA processes?

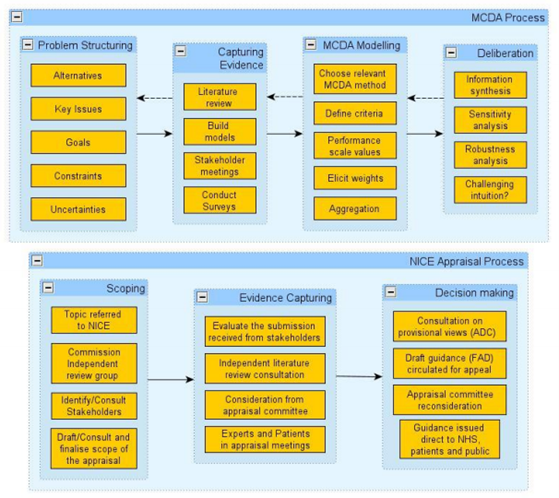

In the UK, NICE has compared the MCDA approach to its current appraisal process (Figure 1) to determine whether it is feasible to include MCDA in its appraisal process. The main difference was seen in the decision-making stage. As stated above, for MCDA evidence should be quantifiable as it will be used in mathematical models. In contrast, during the current NICE process the evidence is evaluated in a deliberative manner using health economic analysis and other criteria.

Current use of MCDA in healthcare decision making and HTA

MCDAs have already been used in Europe and worldwide to inform healthcare decision making. For example, the Lombardy region in Italy has included MCDA in its HTA process to decide on the introduction and delisting of health technologies. Within the UK, MCDA have also been used by a Health England Leading Prioritisation (H.E.L.P) study to prioritise investment in preventative health interventions. In addition, NICE’s highly specialised technology (HST) appraisal process and Scottish Medicines Consortium’s (SMC) Patient and Clinician Engagement (PACE) program for ultra-orphan drugs have features of MCDA processes, though both do not rely on mathematical models.

The challenge of implementing MCDA in HTA

Implementation of MCDA in HTA submission requires identification of criteria that are (a) relevant to decision makers and (b) quantifiable. These criteria should be clearly defined, judgmentally independent and scalable. In addition, they should be relevant to the decision problem, non-redundant, understandable and feasible. The Evidence and Value: Impact on Decision Making (EVIDEM) framework has developed a list of fifteen explicit quantitative criteria that are grouped into four clusters (quality of evidence, disease impact, intervention and economics) and six implicit qualitative criteria. However, it is the ranking of these criteria that still possess a challenge.

Whilst some attributes (e.g. budget impact and economic) readily lend themselves to the numerical approach of MCDA, other attributes are much hard to quantify (e.g. additional benefit over comparator, patient quality of life or care giver burden) and could result in being subjective, potentially undermining the whole approach for MCDA. The transparency associated with MCDA may also pose challenges for payers who may be unable to fund new treatments, whereas previously the not recommended decisions were made on the basis of less tangible parameters.

Manufacturers could consider implementing MCDA in their pricing and market access strategies

In some aspects, it seems that MCDA is an almost natural extension of current HTA processes. As such, it can be anticipated that in future more healthcare decision makers may include MCDA or MCDA-like processes in their HTAs and decision making. Manufacturers may want to consider incorporating relevant and measurable criteria, such as identified by the EVIDEM framework, into their pricing and market access strategies to prepare for the future use of MCDA within HTA and patient access decision making. Even if MCDA is not formally included into HTA the identified criteria are still be important to decision makers and inform their conclusions.

Are payers helping or hindering biosimilar market access?

Given the recent changes to the biosimilar market over the last 5 years with the launch of multiple products, biosimilars are moving from novelties into the main stream. There is a perception that payers are trying to encourage faster access to biosimilars as they have the potential to offer broader access to innovative medicines and reduce healthcare savings. Does the evidence actually support this assumption?

Over the past few years, national payers have introduced biosimilar pricing policies which are less onerous than the pricing and reimbursement requirements for New chemical entities. For example, in UK NICE and SMC does not require a full HTA submission if the biosimilar price is lower than the branded product and access is only sought for indications previously approved by NICE or the SMC. In Germany biosimilars do not need to undergo an AMNOG assessment and are, essentially, considered the same as generics from a pricing perspective. In France, Italy and Spain there is an abbreviated pricing and reimbursement process if the biosimilar is price 25-50% lower than the originator product. Other national level policies have stimulated biosimilar uptake. For example, in Germany, the healthcare insurers have implemented multiple policies which has resulted in biosimilars achieving significant market share including tendered contracts, prescribing share quotas, and automatic pharmacy substitutions (which are strictly regulated, and for naïve patients only).

Other national biosimilar policies are creating unintended barriers to entry for biosimilars and have hampered efforts to shift market share towards biosimilars. For example, in Spain, an internal reference group may be created, which results in the reimbursed price being the same for biosimilar and the originator. This disadvantages the biosimilar as there is limited uptake, as physicians continue to prescribe the originator as there is no price incentive. Whilst capping reimbursement prices to biosimilar levels creates short term healthcare savings it does not encourage the uptake of biosimilars, and such policies could reduce competition over the longer term.

National ‘winner takes all’ tenders are another example where short-term healthcare savings can be recognised, but may have unintended consequences. One example is Norway, where the level of biosimilar discount 69% (for infliximab) and 47% (for etancercept) offered to win the tender creates significant short term cost savings. However, these discounts can set a dangerous precedent, both within the country and for other markets, as payers will come to expect them each year. It is unlikely that the biosimilars manufacturers will be able to maintain this level of discount over the longer term which, again, may result in reduced competitor (and higher prices) over the longer term. Also, whilst biosimilars undergo abbreviated HTA assessment, if the originator product was rejected, or had restricted patient populations for reimbursement, a full HTA process is mandated for the biosimilar. This can be a potentially costly and time resource intensive exercise.

Offering additional discounts to secure hospital access is common across the EU and can result in the actual net biosimilar price being less than 50% of the originator price. This can apply further financial pressure on biosimilar companies. These discounts can have a positive impact on patient uptake. For example, a study in Sweden showed that a discount of 30% was sufficient to place naïve patients on biosimilar anti-TNF. A 50% discount was required before hospitals actively encourage switching of existing patients to the biosimilar, indicating that a ~50% price discount is sufficient to entice both payer and physicians to use biosimilars.

Access barriers for biosimilars are also being observed at the local level. One of the main challenges is physician uncertainty over the value of biosimilars. Whist physicians recognise the need for healthcare savings, their predominant focus is on providing the best possible care to their patients. Unlike generics, physicians are generally encouraged to use brand names when writing prescriptions for biologics. For example, in the UK, the MHRA recommends that all biological medicines, including biosimilar medicines, are prescribed by brand name. The rationale is that biosimilars are not presumed to be identical in the same way as generic non-biological medicines. As such, brand name prescribing ensures that the intended product is received by the patient. This results in the choice of whether a patient receives a biosimilar or originator rests with the physician and pharmacists having to dispense the originator product, even if a lower cost biosimilar is available.

To overcome these barriers and ensure physicians feel comfortable in prescribing biosimilars, it is important to build trust in the clinical value of biosimilar. There two main areas of physician uncertainty regarding biosimilars. The first is for indications where there is no clinical data for the biosimilar, as they are usually approved by demonstrating comparability in only one indication, but they are licensed for all the indications of the originator biological medicine e.g. the use of biosimilar anti-TNFs for treatment of Crohn’s disease.

Biosimilar companies need to convince physicians that the biosimilar is equally effective but in a way that will not significantly increase costs (e.g. conducting additional trials which increases the cost for the biosimilar manufacturer and ultimately the price of the biosimilar). One potential way is to consider investigator initiated trials whereby manufacturers can build trust with physicians whilst at the same time developing a sufficient evidence base to demonstrate the comparability of biosimilars to the branded products. The second concern is regarding switching patients who are currently on the originator product to the biosimilar. The results for the NOR-SWITCH study, which investigated patient outcomes of patients switching to biosimilars products and showed patient outcomes to be comparable will go some way to addressing this concern.

Whilst payers recognise the potential cost savings that biosimilars can provide and understand that it can broaden patient access to innovative medicines, work still needs to be undertaken to ensure that biosimilars can gain a foothold in markets and secure sufficient market share to ensure that the business model is sustainable. Payers need to consider the longer-term cost-savings of biosimilars, not just the immediate short-term budget savings that are on offer. Biosimilar manufacturers need to ensure that payers are well informed on the potential benefits of biosimilars and focus communication on the long-term healthcare savings of biosimilars. It will take time for physicians to feel comfortable using biosimilars. However, if the evidence generation continues, overtime, biosimilars have the potential to be considered comparable to generics (which also faced similar issues when launched) and offer healthcare benefits to a broader patient population whilst reducing overall healthcare expenditure.

Interesting articles that caught our attention

Drugmakers find competition doesn’t keep a lid on prices

Excellent analysis showing how free pricing can actually result in drug costs increasing despite competition https://goo.gl/AKufRh

Early payer scientific advice procedures in the EU: which one is most suited for pharmaceutical companies?

Our recent ISPOR analysis on the benefits of payer scientific advice is available to download. https://goo.gl/zcN3Mm

What puts a new drug launch in line for victory?

Confirmation that major clinical difference, strong marketing strategy and commercial excellence are the key drivers to launch success https://goo.gl/aqcvrz