Patient access to high-cost orphan drugs. How have the Netherlands and Scotland recently adjusted their approach?

The number of drugs approved for the treatment of orphan diseases is increasing in Europe, driven by various regulatory and financial incentives. Orphan drugs have important societal value as they improve patient quality of life and address unmet medical need; however, the high prices of these drugs and their often-weaker clinical data packages presents a challenge to health care systems across Europe. In this newsletter we highlight recent changes to the reimbursement processes for high-cost orphan drugs in the Netherlands and Scotland.

Drug pricing pressure in Dutch hospitals

The cost of hospital drugs in the Netherlands has been a hot topic for several years. In 2013, the Dutch Health Authority stated that hospital drug costs had increased from €690m in 2010 to €1,530m in 2013[1]. In the 2016 Medicines Plan of the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport (VWS), combatting the high price of medicines was one of the major themes, with a focus on the hospital setting[2].

Unlike in the outpatient sector, where the Health Minister decides whether a medicine will be reimbursed, all new hospital medicines have been automatically reimbursed in the Netherlands providing they comply with ‘established medical science and medical practice’. In practice, this has meant that hospital drugs are almost always reimbursed, regardless of their cost.

Since 2013 the Dutch government has also transferred expensive prescription drugs from the outpatient budget to the hospital budget, including the anti-TNFs and cancer medications. In addition, instruments used to apply pricing pressure in the outpatient sector (e.g. the preference policy) cannot be applied by hospitals, and hospitals have limited negotiating power with health insurers.

The Health Minister has therefore considered a range of measures to limit hospital expenditure, including a new policy for high-cost orphan drugs.

A new high-cost drugs policy: the ‘sluis’ (‘lock’) system

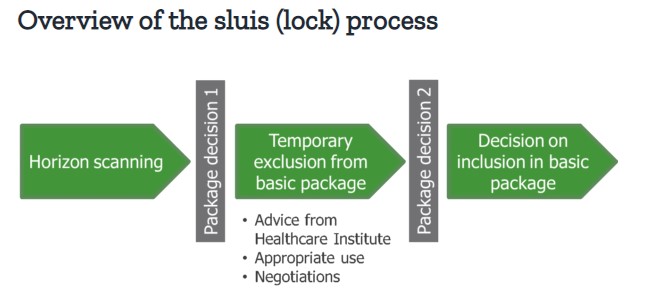

In order to make new, expensive drugs affordable within hospitals, a sluis (lock) system has been introduced, with timeframes and assessment criteria formalised in a government decree, effective as of July 2018[3]. When a medicine has been placed in the lock, its inclusion into the basic package is assessed by the National Health Care Institute (ZIN), based on effectiveness, necessity, cost-effectiveness and feasibility. Measures can then be taken to reduce costs, negotiated with the VWS Ministry. These include appropriate use measures (e.g. the development of treatment guidelines/ protocols, or the concentration of treatment in expert centres) or financial arrangements.

Two criteria are used to determine whether a medicine is placed into the lock:

- Macro cost. If the drug results in a macro cost increase of >€40m per year (the level considered to be ‘high risk)

- Cost per treatment. Hospital medicines that cost >€50k per patient are typically found to not be cost effective. The costs per treatment may be a reason to apply the lock, even if the increase in macro costs is <€40m.

During the lock period, the supplier is permitted to make the medicine available to patients free-of-charge, if desired. Following the termination of the lock, the medicine may enter the basic package unrestricted, with certain financial or use restrictions in place, or with a conditional authorisation. It may also not be permitted to enter the basic package at all.

Drug manufacturers must therefore now be prepared to provide the necessary data to satisfy the ZIN’s assessment, including health economic analyses. In addition, manufacturers must be ready for potential price negotiations with the VWS Ministry, in order to avoid lengthy delays before their drug is included in the basic package.

Inadequate access to ultra-orphan drugs in Scotland

For many years the Scottish Medicines Consortium (SMC) has been made aware that traditional approaches for assessing the value of medicines are not suitable for orphan products. The small number of potential patients leads to higher individual treatment costs, and challenges in achieving standard cost-effectiveness thresholds[4]. In May 2014, following an extensive review, the SMC changed the way that it evaluates end-of-life medicines and medicines to treat small patient populations. Patient and Clinician Engagement (PACE) groups were created to give patient groups and physicians a stronger voice in SMC decision making, and a broader assessment framework was implemented that considered more than just the direct impact of a new drug on patients.

In December 2016 the Montgomery Report was published, assessing the impact of these changes. It concluded that access to end-of-life, orphan and ultra-orphan drugs has increased, but found that only 14% of medicines for very rare conditions were approved despite supportive PACE statements[5]. The report recommended that alternative assessment and approval pathways for these medicines be explored, including the possibility of making all ultra-orphan drugs immediately available, but subjecting them to ongoing evaluation in Managed Access Schemes.

A new ultra-orphan drug assessment pathway to speed up patient access

The Scottish Government responded to the findings of the Montgomery Report by introducing a revised process for assessing the clinical efficacy of ultra-orphan drugs. Such drugs are now defined in Scotland as medicines used to treat very small patient populations; conditions affecting fewer than 1 in 50,000 people (approximately 100 people or fewer across the whole of Scotland).

The changes to the process now mean that any drug meeting this revised definition will be made available on the NHS for a minimum period of 3 years, while further information on its clinical efficacy is gathered. The SMC will then review the evidence and make a final decision on routine use in NHS Scotland. Based on current guidance to submitting companies, the SMC will adopt a broader decision-making framework, examining the nature of the condition, the impact of the medicine, and impacts beyond direct health benefits. The economic analysis will be a factor within the decision-making framework but will not be the predominant factor in the SMC decision[6].

The Netherlands and Scotland therefore appear to have gone in opposite directions in their approach to high-cost orphan drugs. The Dutch Government is seeking to delay market access through the lock system, whereas the Scottish Government is aiming to provide early access to ultra-orphan drugs for a period of several years while additional data is gathered. The effect of these recent changes on patients’ ability to access high-cost drugs in their respective countries remains to be seen.